SaaS pricing and revenue models are evolving and so must traditional SaaS metrics. If we don’t adapt metrics formulas for our revenue streams, our metrics output will be incorrect and misleading.

The CAC payback period is one of my favorite metrics. However, it will lead you done the wrong path if you have subscription revenue and variable revenue streams. Variable revenue streams might include usage, processing, or transaction revenue lines.

If our SaaS revenue profile includes significant variable revenue, we must modify the CAC payback period formula. In this post, I’ll demonstrate how I include variable revenue in the calculation of the CAC payback period.

What is the CAC Payback Period

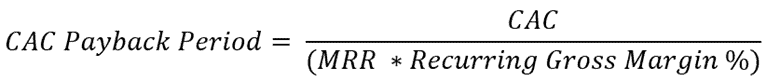

The CAC Payback Period measures the number of months required to pay back the upfront customer acquisition costs after accounting for the variable expenses to service that customer. Simply put, CAC Payback Period equals CAC divided by the gross margin dollars generated by that customer.

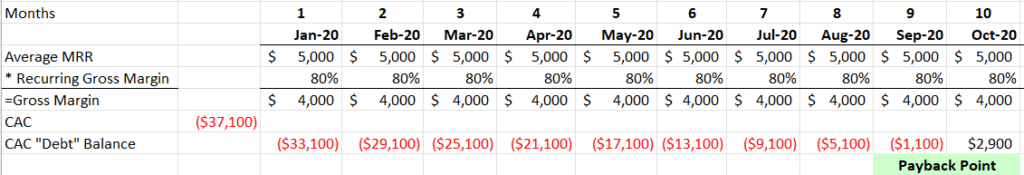

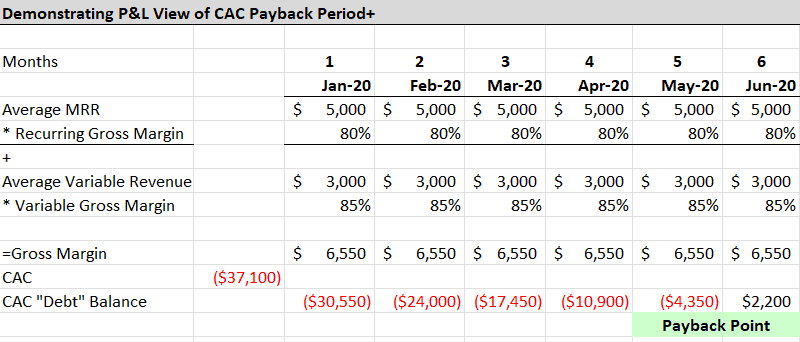

The picture below demonstrates the concept of the payback period. In this example, our CAC is $37,100. After COGS expenses, we have $4,000/month available to pay back the upfront CAC. In this case, we reach the payback point at just over nine months.

The Traditional CAC Payback Period Formula

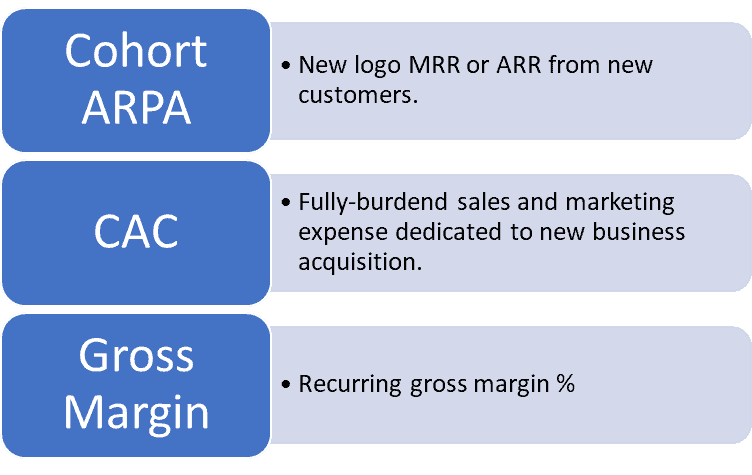

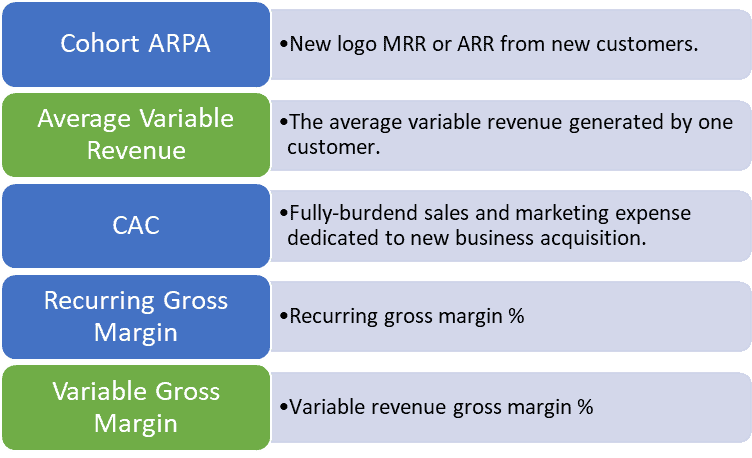

The CAC payback period requires the following inputs. The result of this formula is the number of months to pay back our new customer acquisition costs.

- Logo-based CAC – the sales and marketing expenses to acquire one new customer

- Recurring Gross Margin – we margin adjust the cohort ARPA so that we payback CAC after accounting for SaaS cost of goods sold (COGS)

- Cohort ARPA – the average new MRR or ARR that we receive from a new customer or user. If you use ARR in the formula, be sure to multiply the result by 12 to convert to months.

Traditionally, cohort ARPA included only subscription revenue. That’s fine if all or most of our revenue comes in the form of subscription revenue. If we have significant variable revenue and don’t include it in the formula, our payback period will be artificially high (worse).

If our revenue profile includes subscription revenue and significant variable revenue, the traditional CAC payback period formula will be misleading.

CAC Payback Adjusted for Variable Revenue

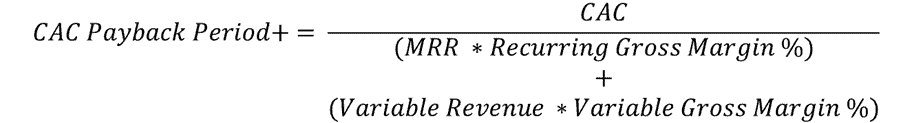

We need two adjustments to the traditional CAC payback period formula to account for variable revenue. First, we need the average variable revenue per customer. Second, we must adjust our gross margin percentage for the gross profit contributed by our variable revenue stream.

I’ll call this adjusted formula “CAC Payback Period +” for simplicity.

- Logo-based CAC – the sales and marketing expenses to acquire one new customer. No change here.

- Weighted-average Gross Margin – we margin adjust the cohort ARPA so that we payback CAC after accounting for SaaS cost of goods sold (COGS). We must now consider both recurring and variable margins. This is a change to the formula.

- Cohort ARPA – the average new MRR or ARR that we receive from a new customer or user. No change here.

- Average Variable Revenue – the average variable revenue per customer or user. This is new to the formula.

The boxes in green below are new inputs to the CAC payback period+ formula.

The example below demonstrates the CAC payback period+ concept. We have the same inputs as the traditional example above, but now we have $3,000 of variable revenue associated with new customers. The payback period decreases from 9.3 months above (MRR revenue only) to 5.7 months below.

The impact is even more dramatic if greater than 50% of your revenue comes from variable revenue streams.

CAC Payback Period Nuances

Average Variable Revenue

At the time of new customer acquisition, you may or may not know the variable revenue that a new customer will contribute. If you have contract minimums or tiers on your variable revenue, you may be able to estimate the average variable revenue that the new customer will contribute.

If you do not have contract minimums, I suggest that you use historical averages per customer. This average could be even more refined by analyzing average variable revenue by customer segments (ICP’s, customer characteristics, etc.)

Churn

Think of CAC as debt. You have a stream of income (customer gross profit) paying off a portion of the total CAC (i.e. debt) each month. If you lose that stream of income (i.e. customer), you still have to make payments on your debt.

This is the hidden burden of churn. If a customer churns early, your next customer or customers must pay off their own CAC and the CAC of customers who have churned (assuming you didn’t pay off CAC yet). Even though you might have a nice customer acquisition rate, you are getting deeper into debt with each churned customer.

The more churn you have, the longer your CAC ties up working capital. This prolongs your path to profitability or improved profitability if you are already there.

Time Value of Money

Another factor is the time value of money. The formula above does not account for the fact that you are paying off CAC over time. A dollar in the future is worth less than a dollar today. If you have long payback periods (>12 months), you may consider this. I don’t see this widely used in practice. However, a CFO at a well-known SaaS company commented that they do factor in the time value of money for long payback periods.

Expansion Revenue

CAC payback does not consider expansion revenue which would shorten the payback period. However, there is a cost to expansion revenue which is not accounted for in the CAC number. Unless you have a product-led growth (PLG) sales motion (there is still a cost to this), adding expansion revenue might skew the payback period. However, it would be an interesting discussion within your company.

Action Items

Download my Excel template below. Enter your numbers to calculate your CAC payback period. If you have significant variable revenue streams, calculate your CAC payback period +. How does that affect your payback period?

As traditional debt can steal away our free cash flow, so can your CAC debt. With a couple of key inputs, you’ll better understand the long-term economics of your SaaS business.

I have worked in finance and accounting for 25+ years. I’ve been a SaaS CFO for 9+ years and began my career in the FP&A function. I hold an active Tennessee CPA license and earned my undergraduate degree from the University of Colorado at Boulder and MBA from the University of Iowa. I offer coaching, fractional CFO services, and SaaS finance courses.